The Cycle of Silence

American Jews and the Holocaust: Part 8

This is the final part of a series. Read part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 6, and part 7.

No doubt the social shunning was incredibly painful for survivors, who had already endured so much, and drove them to seek understanding and social satisfaction from each other. But perhaps one of the most difficult things the survivors faced in the post-war years, and even decades, was their new community’s unwillingness to hear about the Holocaust or their experiences as survivors. When Americans were willing to listen, they were often skeptical, dismissive, or even judgmental of the survivors. In his interview with Life after the Holocaust, Thomas Buergenthal reported, “Nobody really wanted to know in those days about the past. Nobody asked. They wanted to know where I came from, what I did. But it went sort of... It was like asking ‘How are you?’ You know, you don’t really expect to get an answer. No, really, there was no great interest in finding out.”

People were simply not interested; they wanted to get on with their own lives. Even Buergenthal’s aunt and uncle, German Jews who had immigrated to America earlier and took him in after the war, were not interested in hearing about his experiences–they worked hard and took care of him, but they simply did not want to hear. Upon reflecting on why people didn’t ask him about his experiences in the Holocaust, Buergenthal offered an interesting interpretation. The silence was not confined to the immediate post-war years; even in the decades following the Holocaust, Buergenthal’s own children didn’t ask him about the Holocaust and he didn’t speak about it. In later years, when the parents and children did speak about it and Buergenthal looked back on the issue, his wife offered a different explanation that had nothing to do with disinterest: “The kids thought it was so painful that they didn’t want to hear about it. And that’s why they didn’t ask. And I took that to mean that they were not interested, and that they were in fact interested.”

Three-year-old Thomas before the war. Photo: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The children knew little of their father’s Holocaust experience other than how painful it was; afraid of hurting or upsetting him, they didn’t ask about it. Their father, in turn, thought their silence on the subject meant they were not interested or didn’t care. And so the cycle of silence ran both ways, where both parties—the American-born children and their European-born Holocaust survivor father—didn’t broach the subject of the Holocaust because each thought that was what the other party wanted. This idea can be applied beyond a single family and to the general community: many American Jews may simply have been afraid to bring up the Holocaust with the survivors and dredge up all the pain and suffering they had experienced. The survivors in turn may have believed the Americans were not interested at all, which was clearly not always the case, as Buergenthal and his children demonstrated.

Lisa and Aron Derman, Holocaust survivors and a married couple who moved to New York after the war, also shared their postwar experiences in Life after the Holocaust. With his wife Lisa filling in with commentary, Aron reminisced about their American neighbors: “They were afraid to hurt our feelings. They thought that if they’ll start talking about it, they don’t know how we’re gonna react. (Lisa: Exactly...) So, they felt better they’re not going to touch it. Whatever you want to say, you’ll say. And little by little you... (Lisa: You revealed some of it.) You revealed some of it. But they didn’t press to anything. And we weren’t maybe so anxious to tell ’em all the details.” As with Buergenthal and his own children, once again neither side was eager to bring up the Holocaust, and so neither really did.

Not all postwar interactions between American Jews and Holocaust survivors were marked by mutual goodwill. Although this particular incident didn’t happen to the Dermans themselves, Lisa had a survivor friend whose Jewish neighbors wouldn’t let their own children play with the survivor’s children. The survivors felt very bad about being rejected by their American neighbors, and Lisa tried to explain that in those early postwar years, “not so much was known and not so many people spoke up, so there was a feeling that the people that were in the concentration camps, there was something... they survived... I don’t know, doing what? Eating other peoples’ flesh? Or, they are terrible...?”

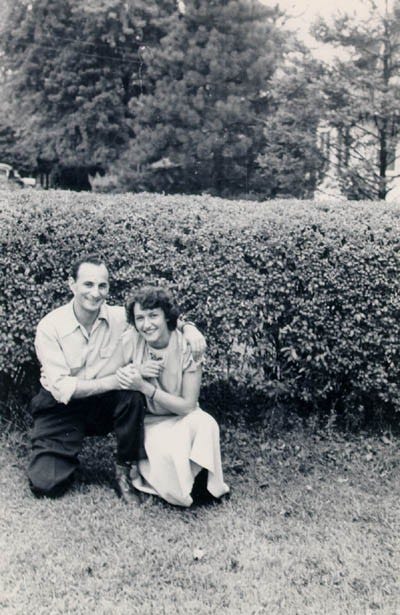

Lisa and Aron in Florence, Italy in 1945. Photo: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

At that time many people didn’t know a lot of details about the Holocaust, but they did know that it had virtually annihilated the European Jewish world and wiped out millions of Jews. The Holocaust system which the Nazis had labored to build was murderous and powerful; some, therefore, believed that those who had managed to survive must have done something bad, or collaborated in some way with the Nazis, to make it through alive.

Other survivors faced the same judgmental stereotypes from American Jews who had the audacity or tactlessness to confront them directly with their judgments. In New Lives: Survivors of the Holocaust Living in America, author Dorothy Rabinowitz shares the testimony of Elena, who went to live with her American cousins in the Midwest after the war. She described them as kind people who kept their distance from her, explaining: “You understand, the concentration camp experience is nothing that endears you to people. People who came to my cousins’ house used to ask me such things as whether I had been able to survive because, perchance, I had slept with an SS man. And if I had, did they think I would tell them?” What could have bred the chutzpah to ask such a crude question? Only an utter lack of understanding of the horrifying magnitude of the Holocaust and what its victims and survivors had undergone, and the difficult choices they had been forced to make.

Perhaps even more hurtful to the Holocaust survivors was the condescension and superiority with which American Jews sometimes treated them. One survivor profiled by Dorothy Rabinowitz, Emil Wolf, faced this as he tried to adjust to life in the United States. His aunt, with whom he stayed, was very upset over the destruction of their shared family in Europe, but otherwise she and her husband “wanted to think no more about the dark experiences they had known themselves in Germany, or the far darker imaginings they had of the things that occurred to those who had stayed when they had left.” Like so many other American Jews, they wanted to get on with their lives as comfortably as possible after the war without having to reckon with the horrors of the Shoah that had destroyed their family.

Worse for Emil, however, were his interactions with the social workers and psychiatric counselors who were supposed to help immigrants. Emil “loathed the probing, personal questions, and the superior air of the questioners…As far as he was concerned, they were not…entitled to hear everything they wanted to know about him, to treat him as though, beyond question, they were his superiors.” These professionals who were tasked with helping Emil work through his problems and adjust to his new life treated him as inferior, and as if they had an intrinsic right to know personal details about his life, as if they were superior to him because he was a victim and they were not. They were condescending and made him feel as if they were doing him a great service, for which he had never asked, and he should feel grateful.

One man asked Emil if he felt guilty: “I mean guilt about survival; you don’t feel upset from time to time that other people in your family died and that you lived?” The thought that he should feel guilty about having survived the Holocaust had never occurred to Emil; it had to be suggested to him by an American stranger, supposedly a professional, who presumed to suggest how it should feel to have survived the Holocaust.

Other survivors, too, refused to feel guilt even when outsiders expected them to. Lisa and Aron Derman confirmed in Life after the Holocaust that they had never felt guilty about surviving and couldn’t understand why some others did or why they should be expected to. Lisa explained it poignantly: “I know that my parents, most of all, most of all in their life wanted us to live! If only I could tell my mother that I survived, how happy she would have been to know that I survived. My father, too. That’s all he wanted us is to live, is to live. So why should I feel guilty?” The Dermans, like other survivors, were simply human beings trying to build decent lives after enduring unspeakable horrors at the hands of the Nazis. No one who hadn’t suffered through the Holocaust, and made the difficult life-or-death decisions it forced on people, had the right to judge them.

The issue of American Jews’ reactions to the Holocaust, both during and after the war, is obviously complex. American Jewry is not and never has been a homogenous community, but certain generalizations can be made for the sake of clarity. The American Jewish community was different from any other Jewish community in the world. While they certainly had to contend with harsh antisemitism, which bettered or worsened with the times, they were relatively secure in the United States. This only improved with time, as new generations of Jews were born and raised in the United States and comfortably asserted themselves as confident Americans. Many secularized, while others kept their religious traditions. Their identity as confident Jewish Americans defined their reactions to the Holocaust: from their communal reaction to Kristallnacht, to the way they received and treated survivors after the war. While they were Jews, they were Americans first, and this differentiated them from the European Holocaust survivors. They had been on the winning side of the war, and many had fought and died for the United States in that war. They did not and could not understand what it had been like to live through the absolute horrors of the Holocaust.

When Holocaust survivors settled in the United States, many American Jews tried to help them by encouraging them to find work, get settled, and assimilate as quickly as possible. But this came at the expense of what the survivors actually needed: a community that was willing to try to understand what they had been through. Individual experiences varied, and certainly they were not all negative. Regina Gelb, who came to the United States as a teenager, emphasized how different her experience was from other survivors’ because of her youth: “I was so lucky to come here and to be a young girl in America, you know? I was just so lucky…I came here, I hadn’t lived yet. So everything that I lived was great!” For plenty of fortunate survivors, America provided the opportunity they so badly needed to live and grow. The experiences of the less fortunate ones, who were not warmly embraced by the Jewish community or given a willing ear to hear what they had gone through and understand what they needed, must serve as a lesson for the future.

I have really enjoyed reading this series. Thank you!