A pogrom, a poem, and a promise

Bearing witness to horrors in 1903 and 2023

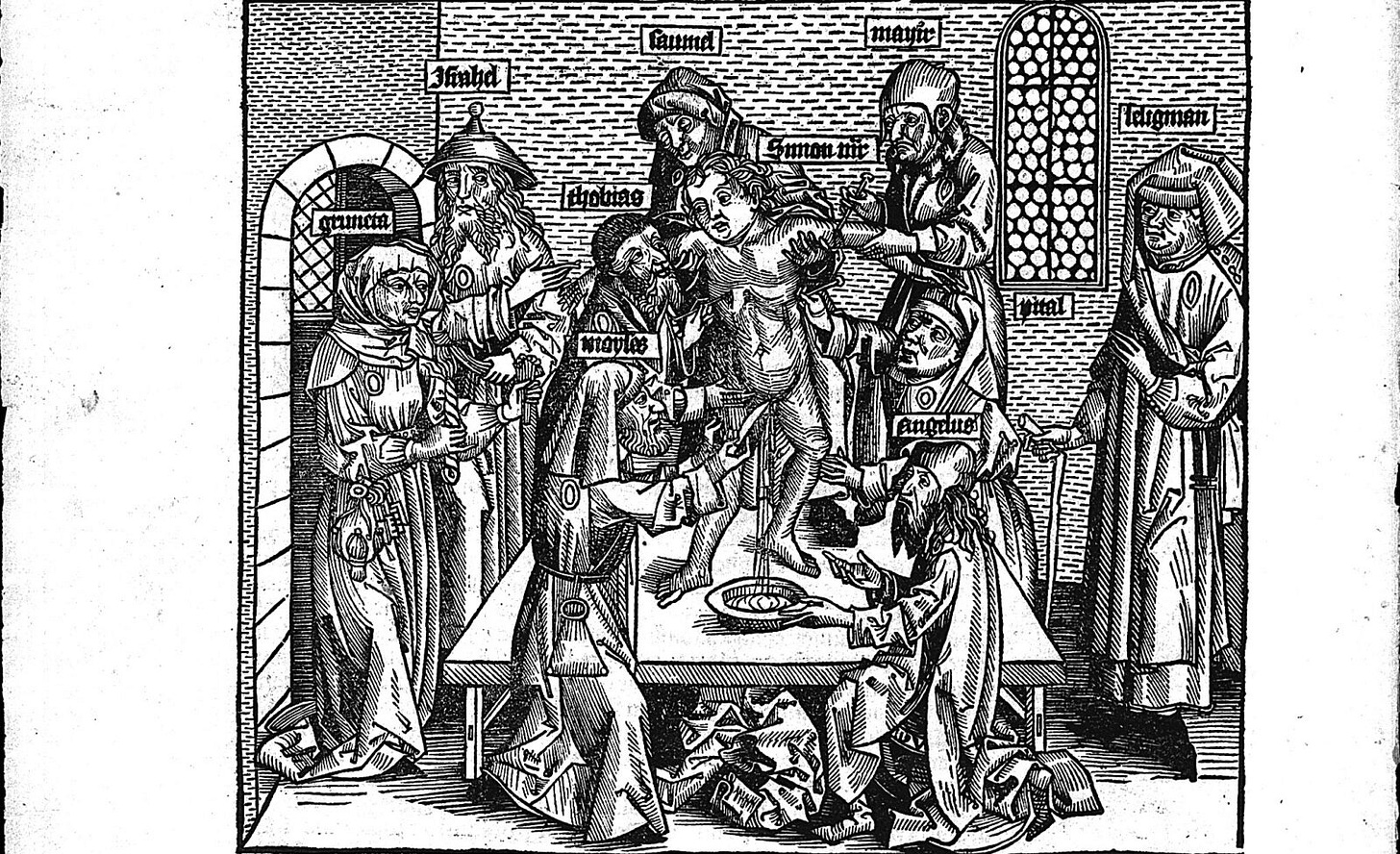

It began with a blood libel, as these things usually did.

This time the setting was Kishinev in Tsarist Russia, today’s Chisinau, the capital of Moldova. It was 1903 and the city was home to tens of thousands of Jews. The antisemitic press loved to stir up hatred of the Jews with propaganda and lies, and this time they had a whopper: that the Jews had killed Christian children to use their blood to make matzo for Passover. It was an old lie but it still proved effective.

Photo: Page from The Nuremberg Chronicle: “Blood Libel,” Germany, 1493. Collection of the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

The orgy of violence lasted for days. The frenzied attackers murdered 49 Jews, wounded many hundreds more in creatively savage ways, raped at least 600 women, looted and destroyed homes and businesses, and left thousands of families homeless.

It was only the latest in the parade of violence that Jewish communities had suffered in a long list of forced conversions, expulsions, and massacres. Jews had always had a precarious existence in Russia (and, frankly, everywhere they have dwelt, to varying degrees, throughout their long centuries of exile). In Russia they had to contend with restrictions on where they could live and what they could do, the kidnapping of their sons for forced service in the army, and periodic flareups of violence that could leave them homeless, beaten, raped, or murdered. These factors spurred waves of immigration of Jews from Russia to Western Europe, Palestine (then a neglected backwater of the dying Ottoman Empire), and the United States at the turn of the century.

But something about Kishinev shook the world.

American Jews, who until then had mostly been content to keep their heads down and get on with the business of building their lives and raising their families, organized protests and demonstrations. They delivered a mass petition protesting the slaughter to the State Department when Russian authorities refused to receive it.

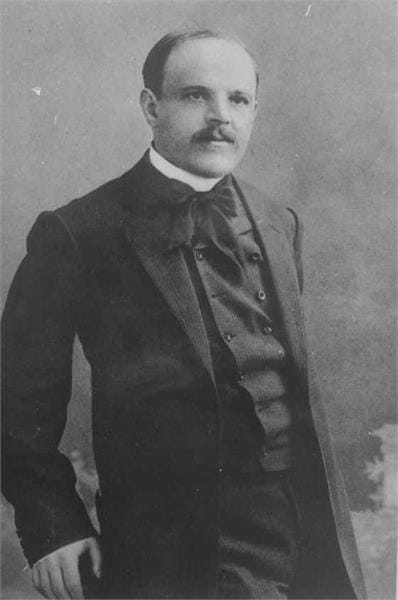

The poet Chaim Nachman Bialik had turned 30 that year and was already known as one of the greatest Hebrew writers of his generation. At the behest of Odessa’s Jewish Historical Commission, he traveled to Kishinev after the pogrom to interview survivors and document what had happened.

Photo: Jewish National Fund photo archive.

His response, “In the City of Slaughter,” is worth reading in full. He wrote it in Hebrew, the Jews’ ancient language that had long been reserved for prayer and literature through centuries of exile and only in recent decades had, through the will of some determined men and women, undergone the extraordinary revitalization that would make it the spoken tongue of the Jews once again in their native land.

The poem cries out to the reader to bear witness, to know what happened in Kishinev. The images are stark and haunting: spattered blood and dried brains. The smell of new blossoms mingling with that of blood. The sunny weather of the incongruous spring that saw such slaughter. The Jew and his dog murdered with the same axe and flung onto the same heap. The baby searching for milk at the breast of its slain mother.

My Hebrew isn’t good enough to read the original, but even in translation, Bialik’s anguish burns through the page. And it’s not just anguish at the brutal fates of the innocent victims and at the evil men who did such things. His verses drip with contempt for those Jews who, in his telling, cowered and prayed and watched from a dark corner as their women were raped. How could they, the “sons of the Maccabees,” bear such shame, to do nothing in face of such a crime and then run to consult their rabbis on a question of Jewish purity law?

Daniel Gordis writes of this scene in his moving book Israel: A Concise History of a Nation Reborn:

It makes no difference, of course, whether the scene as Bialik describes it ever took place. He was, after all, a poet and not a historian. What matters was his horror, both at what Europe was capable of doing and—because of the passivity that Jewish tradition had fostered in them—at what the Jews could not do.

…For Bialik, therefore, and for many of his contemporaries, the point of Zionism, of the return to the Jewish homeland, was not simply to create a refuge or to fix the “Jewish problem” in Europe. The reason that Jews needed to return to their land was that it was only there that the Jews could fashion a “new Jew.” It was time, he insisted, to re-create the Maccabees of old. It was time for the Jewish nation to be reborn.

Israel was the answer. Only in their own land could they be free to control their own destiny. Only in a nation of their own could they take whatever action necessary to protect Jewish lives—action that the rest of the world had proven it would not take. In the decades since Israel’s rebirth as a nation in 1948, some have claimed, out of ignorance or malice or antisemitism or some combination, that Israel was created because of the Holocaust. But that has it the wrong way around. The Holocaust, decades after Bialik wrote his searing poem, tragically confirmed what Zionists had long declared: that Jews needed to be free to decide their own fate in their own land, to fling open the doors as a refuge for the world’s Jews, to make the hard choices necessary to defend themselves and their children.

The Jewish state would be the only thing that could make the much-bandied-about slogan “Never again” not just empty words, but a promise.

And then the unimaginable. A pogrom of unimaginable scale and brutality. But not in 1903, a world without a Jewish state, and not in Tsarist Russia, but in Israel itself.

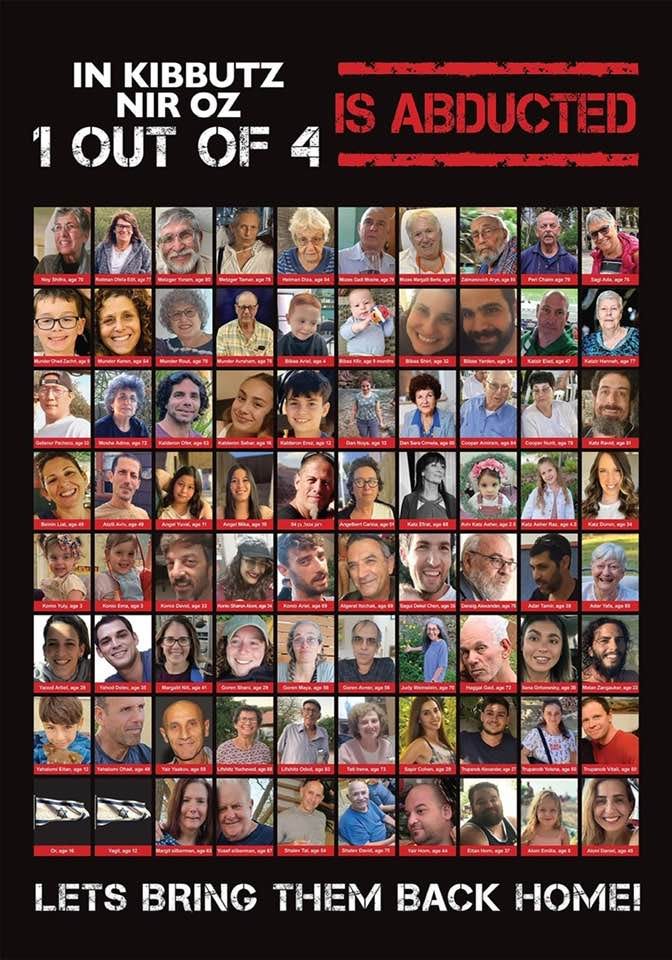

Is pogrom the right word to describe what happened on October 7, when Hamas and other Palestinian terrorists poured across Israel’s border in search of Jewish blood? Massacre. Slaughter. No noun feels right. Adjectives, too, fail. Brutal, savage, barbarous. Nothing is enough. It’s been more than two weeks, and hundreds of victims’ bodies still aren’t identified. Hundreds remain hostages in Gaza, children and elderly among them.

New details constantly emerge about what the terrorists did in this bloodbath, the worst massacre of Jews since the Holocaust. The crimes are unspeakable, but we must speak about them anyway. If nothing else, we can bear witness.

They carried plans instructing them to kill as many as possible, to use human shields, and to target schools specified by name. They slaughtered defenseless infants. They tied up children and their parents before burning them alive. They ripped open a pregnant woman and murdered her unborn child. They raped an untold number of women. They tortured, mutilated, and beheaded Jews. In 2023.

There were heroes, too. These Israelis were not the cowering men of Bialik’s poem. Parents hid their children in safe rooms and died fighting off the terrorists so that their little ones might live. Arab Israeli paramedics labored to save lives and lost their own in the process. A retired IDF general rushed south to save his son and his family who were under siege, fighting off terrorists and helping other survivors along the way. A 25-year-old kibbutz security coordinator led her fellow kibbutzniks in killing dozens of terrorists who had infiltrated their home.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Kishinev in the past two weeks (and I’m not the only one—I’ve seen it referenced recently in several essays and articles). Kishinev was a flashpoint for Jews and all who cared about humanity or civilization or basic decency in 1903 and for decades that followed. Its effects cannot be overstated. Kishinev, and Bialik’s anguished poem memorializing what happened there, seared the conscience and demanded recognition, memory, action.

I studied Jewish history, and I knew about Kishinev, but I was stunned a week or two ago to come across a reminder of the number of Jews who were killed in that pogrom: 49. Because day after day following October 7, I had watched with horror as the number of estimated dead from the massacre in southern Israel mounted: from 150, to 200, to 400, to 700, to 900, to 1,200, to over 1,400. And in Israel, where this wasn’t supposed to happen. How could this have happened?

I’m certainly not the one to answer that question. There will be reckonings of intelligence and security failures that allowed this catastrophe to happen. I’m not qualified to assess any of that.

But I can bear witness. To the evil that terrorists committed against innocent men, women, and children because of the hatred for Jews that consumed their hearts and rotted their brains, the world’s oldest hate that still hasn’t died. To the trauma of living Israelis—Holocaust survivors and their IDF veteran grandchildren, immigrants from all over the world, secular kibbutzniks and Haredi scholars volunteering for the IDF—reckoning that it can, in fact, happen in Israel, too. To the moral bankruptcy of the ghouls who celebrated the terrorists’ slaughter of Jews as a victory of “resistance” and “decolonization.” To the media outlets who, as the victims of Hamas’s bloodbath were still being tallied, rushed to print that same terrorist organization’s false accusations about Jews killing innocents on their front pages (yes, that same blood libel where we started).

For those of us outside Israel, who do not have to put our lives and those of our children on the line not out of some ideology but out of a simple battle for existence, bearing witness is the least we can do.